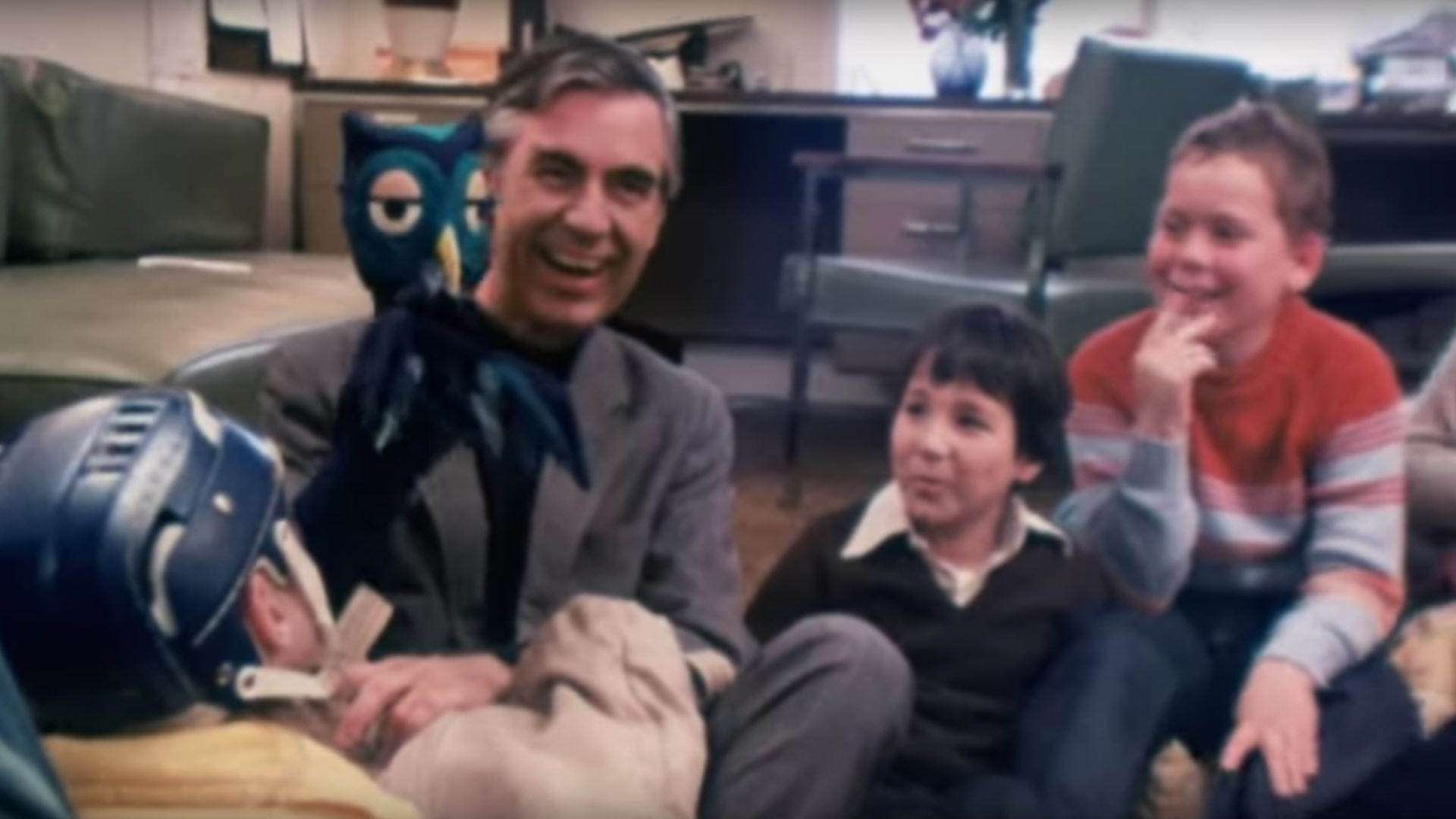

Don’t let the comfy sweaters fool you: Fred Rogers was so much more than a nice man. Here, Content Curator Beau Denton (MA in Counseling Psychology, ‘17) writes about the new documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, the magic of fiction, and the surprising ways Mr. Rogers might shed light on how we relate to ourselves and each other—including those who are different from us.

I expected much of how Won’t You Be My Neighbor moved me. I watched in tears as Morgan Neville’s beautiful film showed Fred Rogers’ seemingly endless capacity for empathy and compassion, and I choked up at the all-too-rare gift of an adult who remembers what it’s like to be a kid. I was inspired by his defense of quiet kindness in media, energized by the subtly subversive advocacy woven through his show, and grieved by the ways that his advocacy fell short (like when Rogers told his friend, Francois Clemmons, that he could not remain on the show if he came out as gay). I was angered by the pushback to Mr. Rogers—those who say he couldn’t possibly be genuine, or the right-wing commentators who skewed his “you’re special just the way you are” message as one of entitlement, claiming that he ruined a generation by insisting on the God-given beauty in each person.

I don’t want to minimize what a gift all of the above is; the film is worth seeing on those merits alone. But I would like to focus on something else, something that surprised me and has stuck with me for days after leaving the theater. First, though, a story.

***

When I was in middle school, my English teacher assigned The Wizard of Oz and lectured about the use of symbolism and metaphor, arguing that the whole text could be read as a commentary on political issues of the late 1800s: the plight of farmers, the intrusion of business magnates and politicians from the east, the movement to keep the rate of the dollar fixed to the value of gold or silver.

By this time I had long been a fan of the Chronicles of Narnia and the lion-Jesus that stalked its pages, but I had never tried writing an allegory myself; my stories up to that point comprised a Hardy Boys-inspired series about me and my brother called, originally enough, the Denton Boys.

This was in the year after 9/11 and the run-up to the 2004 election. It was the first time I remember being curious about the U.S. political system, at least as it was filtered to me through my parents and my conservative Christian school, and I was intrigued by the idea of crafting a timely political allegory.

My story was about a bold and handsome history teacher who drove a Chevy pickup. His name was Mr. Smith, and he was often seen carrying a baseball bat—you knew right away that he was confident and tough, an all-American embodiment of everything I thought a man was supposed to be.

One day, Mr. Smith and the other teachers learned that one of their students was being abused at home. A debate ensued in the staff lounge. Mr. Smith wanted to go to the boy’s house and teach his parents a lesson; Mr. Pierre, the French teacher, insisted that it was none of their business and they should stay out of it (worth noting that this was smack dab in the middle of the “freedom fries” era).

The principal, Unifred Nattings, decreed that they needed more time to talk about it before deciding the best course of action, but Mr. Smith would have none of that. He called his gorgeous wife to say he loved her, then grabbed his bat and ran to his truck, which spewed gravel and dust as he peeled out of the parking lot. That’s where the story ended—no need to write any further, because the righteousness of Mr. Smith’s actions and the certainty of his victory were so evident.

My political inclinations have shifted quite a bit since middle school, and I’d like to believe that I now have at least a little more appreciation for nuance and subtlety. But that initial intrigue with symbolism and metaphor remains, an enduring fascination with the ways we express that which we don’t know how to express.

***

Here’s what surprised me about Won’t You Be My Neighbor, what I haven’t been able to stop thinking about: Mr. Rogers wrestled, at times, with profound insecurity. I remember reading somewhere that he had been insecure as a child and had experienced bullying, but I must have assumed that—even though I don’t hold this expectation over anyone else—he had grown out of it. His gentle strength, his quiet conviction, his steady faith and unflinching kindness: how could a man like that be so anxious about how his work would be received, or worry so intensely about living up to people’s expectations?

In a particularly telling scene, one of his children reveals that, when Rogers needed to act at home in a way that was un-Mr. Rogers-like, he would take on the voice of one of his puppets. The implication is that, in moments of conflict or discomfort, Fred Rogers was terrified of remaining in his own skin and would, instead, assume the identity of a character.

That moment (questionable parenting tactics aside) immediately brought me back to the middle school boy who was so intrigued by allegories and symbols, so comforted by the idea of using fiction to communicate that which he did not otherwise dare reveal. My days of Bush-era fanfiction had been mercifully short-lived; instead, in high school, I started writing stories in which the most damaged and insecure parts of myself were free to roam. I dreamed up characters who said all the things I couldn’t say, imagined worlds in which I could be brave and articulate and wise.

I sobbed there, in the theater, as I wondered if Mr. Rogers had been doing the same thing all along. He imagined a simple but vibrant world and filled it with characters who embodied different parts of himself, parts that he may have been too anxious to live into without a little separation, a little space created by fiction and imagination. He put on his puppets and projected his voice into them, giving language to the expressions of himself that he had learned to silence and hide as a child. This imagined world was not divorced from reality, and it did not make Rogers less of himself without the puppets. It was, like all the best fiction, a space where he could wrestle with real-life concerns and wonder about real-world issues in new ways, inviting millions of others to do the same.

“He put on his puppets and projected his voice into them, giving language to the expressions of himself that he had learned to silence and hide as a child.”

I wonder, if Fred Rogers had somehow “grown out of” his insecurity, would he still have that remarkable capacity for remembering what it’s like to be a child? If he did not find ways to give voice to the parts of himself he was ashamed of or anxious about, would he have still resonated with so many children from such diverse backgrounds?

I wonder, too, what our world might look like if more of us kept our childhood selves in mind more often, if we did not act as if our own insecurities and anxieties were things of the past. Would we still be capable of separating immigrant children from their parents in the name of self-protection if we remembered something of what it’s like to be scared and alone as kids, if we stopped pretending we are not sometimes still scared and alone as adults?

Our distance from childhood is not just a problem of memory; it is a lie we tell ourselves and each other. I’m grateful to Mr. Rogers for reminding me of this, and I believe—I have to believe—that there are others like him in the world. Through fiction, art, music, whatever it takes, I pray that we acquaint ourselves again with the beautiful, anxious, lonely world of childhood, that we find new ways to give voice to the parts of ourselves we have hidden, and that this deepens our empathy and compassion for the people around us, no matter who they are.

https://youtu.be/x6XAP_VThhk