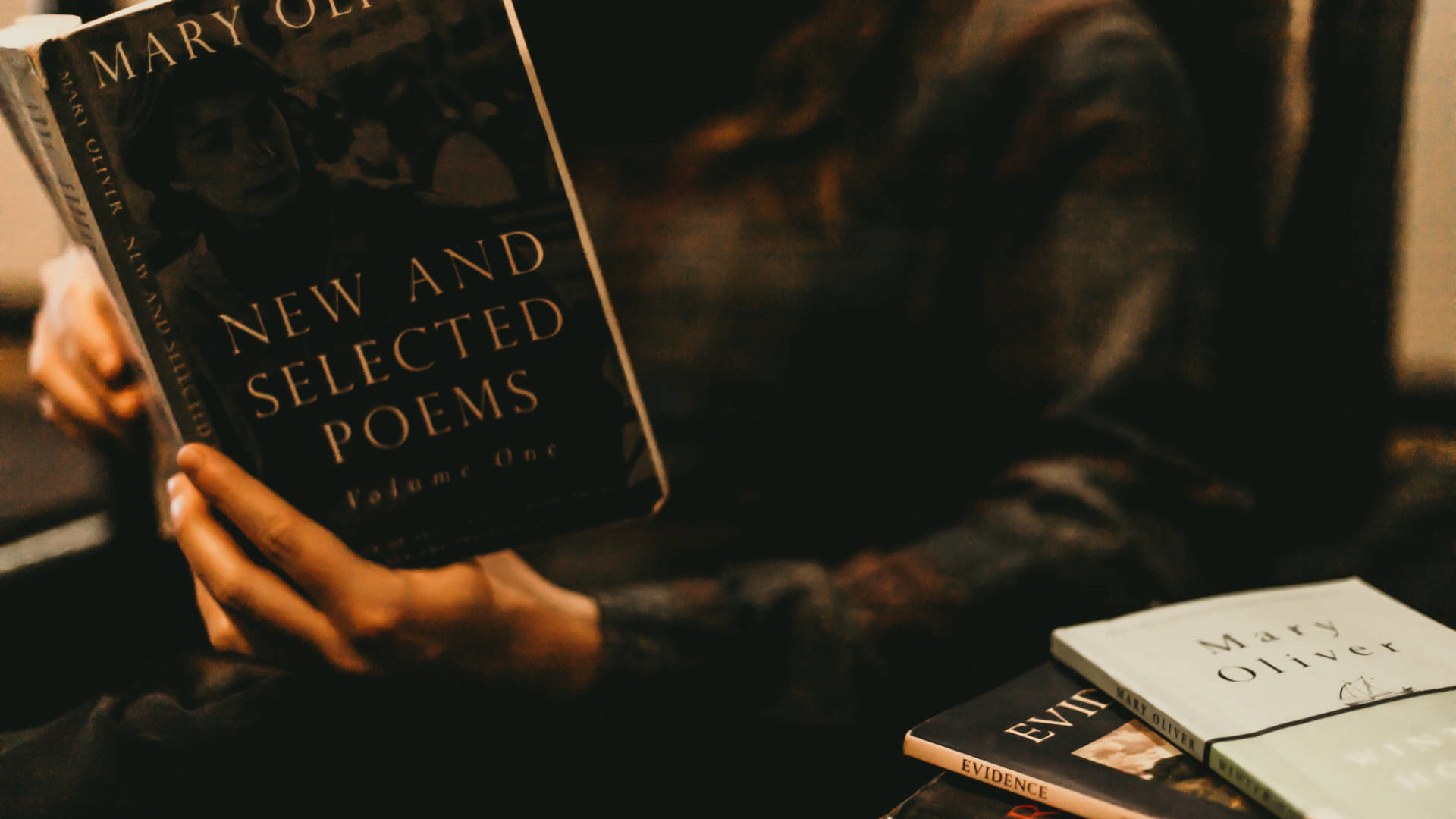

Artists often occupy a prophetic role in culture, speaking truth, beauty, and goodness into a world desperately in need of them. They help guide us to those thin places where the gap between what is and what could be is not quite so daunting. The poet Mary Oliver lived into this call with a grace and generosity that endeared her to readers for more than 50 years. Here, Beau Denton (MA in Counseling Psychology, ‘17), Content Curator, reflects on the gifts Mary left us with, and on why she might have resonated so deeply with many in our community.

“Instructions for living a life:

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.”

–Mary Oliver

On January 17, for just a few hours, part of our collective online life seemed to take on a different tone. The usual frenzy was jarred by news of Mary Oliver’s death, and as word spread it set the Internet afire with grief and gratitude and poetry. Given the storms underway around us and the anxious pace of our discourse, Mary’s quiet prevalence that day reflects something of how unique she was, how holy the gifts she left us.

In my corner of the Internet, this phenomenon was especially noticeable among my Seattle School friends and colleagues—because few voices have seeped into the pulse of this community so thoroughly and so generously. Of course, certain writers shape a pivotal moment in particular classes: first-year students often develop a begrudging affection for Martin Buber and his fondness for talking to trees; Harry Middleton’s gorgeous memoir The Earth Is Enough prompts an assignment with which Dan Allender’s students are on a first-name basis; in theology classes, many students bond in common conviction and inspiration under the work of James Cone; and Annie Rogers’s A Shining Affliction is a beloved rite of passage in the Counseling Psychology program.

Fewer writers, though, manage to impact the rhythms and tones of life in our red brick building even when they are not officially assigned in class. And perhaps none have done so with as much resonance as Mary Oliver—a matriarch of The Seattle School whose words stir somewhere deep in the heart of this place.

With the authority of a voice at home with itself, Mary called us to listen and pay attention. Sometimes her call came as a gentle whisper, and other times it felt more like a slap in the face: look up, at the gray sky you take for granted; look down, at the wet soil knotted with roots; look in, at the self you have forgotten. In a way, she was echoing that other Mary, who teaches us that even the bravado of wise men and the chaos of exile might evoke in us a moment of attentive pondering.

“In a way, she was echoing that other Mary, who teaches us that even the bravado of wise men and the chaos of exile might evoke in us a moment of attentive pondering.”

But attention itself is not the goal, which Mary described learning from her long-time partner Molly: “Attention without feeling, I began to learn, is only a report. An openness—an empathy—was necessary if the attention was to matter.” It’s why her famous “instructions for living a life” don’t end at “pay attention,” though that is the crucial point from which everything else follows. Instead, attention leads to astonishment, and astonishment turns us toward others. It seems that the work of paying attention and opening ourselves to wonder is not complete until it also deepens our capacity for love.

Love, then, is where Mary leads us, and it’s why the Internet, for just a moment, felt like such a kind place on that sad day. Because so many of us, in one way or another, learned something from Mary about what it means to love. In the profound simplicity of her work, she assured us that love is not resounding gongs and clanging cymbals. In her long, inquisitive walks she proclaimed that presence and attunement are the elements of love, and that those are grown through the repetition and discipline of ritual. And in not shying from grief after her partner’s death, she reminded us that love can be excruciating and raw—that it sometimes comes as a gift in “a box full of darkness.”

Mary taught us again and again that love is most fully itself when it is omnidirectional: outward, inward, up, down, around—each avenue nourished by and dependent upon the others. If you treat the “soft animal of your body” with impatience and contempt, she seemed to be asking us, how can you hope to love others any differently? If you stop listening to the earth and all that breathes and pulses around you, how can you maintain the intrigue that gives love wings? And if you are not at home in your own self, will you ever be home anywhere else?

Somehow, when Mary’s work asked big questions or spoke a truth that shot like lightning through our bones, it never felt as if she was lecturing or preaching at us. She offered a small thing well said, a bit like walking on the beach with a friend who stoops to collect a seashell. “Here,” she says, dropping it into our palm, “look what I found.” Then she’s off, continuing her walk and letting us decide what to do with her gift.

That is why she could reach refrigerator-magnet-level prevalence and still feel as if she was speaking directly to you, her reader. When she said, “You do not have to be good,” it was both a universal proclamation and the close comfort of a dear friend, offering a cup of tea to bring our anxious frenzy back to the earth. She was both wise teacher and gentle companion.

There are some who were skeptical of this, who believed that Mary’s presence on Pinterest and postcards must mean her work was somehow less beautiful or important. Her critics often championed the suspicious belief that popularity betrays a work as shallow or false, like the easy pleasure and empty insight you might find on Top 40 radio. But I would argue that Mary’s widespread resonance was deeper than that. She saw something true of our world and ourselves, and she offered it to us as a free gift—simply wrapped, shyly given, no strings attached. And we loved her for it.