This series of student work from a recent elective course offered to all our graduate students is a window into the integration and intersections that are created in our curriculum and our classrooms at The Seattle School, not only theology and psychology, but also social justice, ecology, local context, and individualized research. This essay from Emily Knorr, who graduated with her Master of Arts in Theology & Culture in 2023, is the first in the series. For more in this series see Ecotheology: An Orca’s Perspective & Ecotheological Connections: Protest and Celebrations.

An introduction from Dr. Kj Swanson, affiliate faculty spring 2023:

This spring, sixty students participated in TCE 544O Triune God & Creation, an introduction to ecotheology and its relevance within diverse theological, cultural, and global contexts. Our primary texts centered the voices of female theologians from the global south and other perspectives often under-represented in theological and ecological engagement. We also journeyed with Tricia Hersey’s Rest is Resistance (2022) as a companion text, helping shape our imagination around rest as liberatory and vital for humanity, but also for all planetary life and relationships. Each week, we wrestled together not just with the grief over how we have gotten to the climate crisis we are in, but also what it means to try to envision healing—that it’s difficult to work towards a vision you haven’t let yourself dream is possible. I’m pleased to share some of the insightful and hopeful work students created.

Here, Emily Knorr, 2023 MATC graduate, reflects on her Film Response assignment, where students viewed a film through ecotheological perspectives to explore the ways that filmmakers, as cultural storytellers, are engaging and depicting issues of ecology and society. The Last Black Man in San Francisco (2019) was one of the film options that, while not explicitly addressing ecological issues, creatively and thematically depicts experiences at the heart of ecojustice and community.

Film Response assignment by Emily Knorr, Triune God & Creation Spring 2023

Midway through our Triune God class, we were tasked with analyzing a film through an eco-theological lens. A friend texted me and said, “Do you want to watch The Last Black Man in San Francisco? I’ve never seen it but it’s about home so I thought of you.” Throughout our course we were working towards our final project of Envisioning Planetary Solidarity. For me, this process of imagination begins with a rooted sense of place. Our connection to our place or lack thereof determines how we see the present and imagine our future. The home is where my eco-theological questions begin. My friend’s words were all I needed to commit to this film. The Last Black Man in San Francisco is a letter of belonging to a home loved and lost. But it is also a warning of what is at stake if we sever our relationship to our context and to the act of remembering what once was. In our amnesia, we are restricted in our imagination of what our home and neighborhoods can still become.

If you are unfamiliar with The Last Black Man in San Francisco, I will summarize it here the way I did in my analysis:

Pushed to the very edge of San Francisco by gentrification, Jimmie and his best friend set out to reclaim his historic childhood home that was lost to his family due to back taxes. Fighting for his dream of reunification with a home that holds his stories, Jimmie grapples with how to exist between the hope of returning and the reality of displacement. As he tends to a changed San Francisco, Jimmie is confronted with the grief of losing a place you love before ever having the chance to say goodbye. The film deals with complex themes of identity, displacement, belonging, and the power of storytelling.

As I watched the film and completed my analysis, I was struck by the parallels between Jimmie’s deep love for his neighborhood and my own while also reckoning with the many differences that my racial and economic privileges have allowed me when it comes to freedom and agency to stay or to leave. One cannot be acknowledged without the other. This fall, as I return to this assignment completed earlier this year, I think mostly of the warning of the film and a little about the hope of why this work of restoring our connection to home is worth pursuing.

Throughout the film, Jimmie is constantly playing between the fantasy of returning home and the reality of it always being out of the realm of possibility. While the viewer is introduced to the old Victorian home that occupies Jimmie’s dreams, we also begin to see his devotion to the home through his careful attention and caretaking despite his lack of ownership. Day after day he returns with determination to clean up the garden, repaint the windows, and restore the woodwork. In an effort to rid themselves of the inconvenience, the new homeowners try to convince Jimmie that plenty of other houses in the neighborhood look worse. This is where the warning begins. The homeowners are irritated by the intrusion and confused by Jimmie’s commitment. They are detached from the house and disconnected from the story of their neighborhood, surrendering both their own belonging and their agency to create, repair, and restore. But for Jimmie, the story and the context are all he can see. Our local housing crisis has replicated this dilemma of distancing ourselves from the place we reside until home is reduced to a structure needed for survival rather than an unfolding story to take part in. Both can be true. But the decontextualization that occurs in the distancing lays the groundwork for many assaults on the ecological equilibrium of the neighborhood.

Reflecting on the warning of this film led me to ask a few questions about purpose. Why is a sense of rootedness in a particular place, a home, worth cultivating? And what is severed when we lose that sense of place? Later on in the film, Jimmie temporarily gains access to live in his family home for the first time since losing it. The power of this reunification is made clear while he is sitting at the breakfast bar talking to a friend about how he can not wait to read the newspaper. His friend doubtfully points out, “You don’t read the paper.” Jimmie responds, “I’ve never had a home to read it in.” This is the power of home. Entering into a reciprocal relationship of belonging with a place both awakens dormant dreams and builds the foundation required to evolve again and again. A home that holds your stories is a safe place to land so that you can turn towards your neighbor and listen deeply to what the neighborhood is trying to say. In this reunification, there is hope. After many years of dreaming, remembering, and longing, Jimmie was able to feel at home within the walls of the house that had been taken from him. I wonder what our ethical commitments are to our homes, both the houses that we inhabit, the land that we occupy, and the neighborhood we exist within. Is it not our job to be the caretakers of the ecosystems we live within? Who else will steward the stories of our past by tending to the needs of the present in the places and spaces where we live? Who will bear witness to the little losses all around us that are changing the landscape of our neighborhoods? Who, if not us?

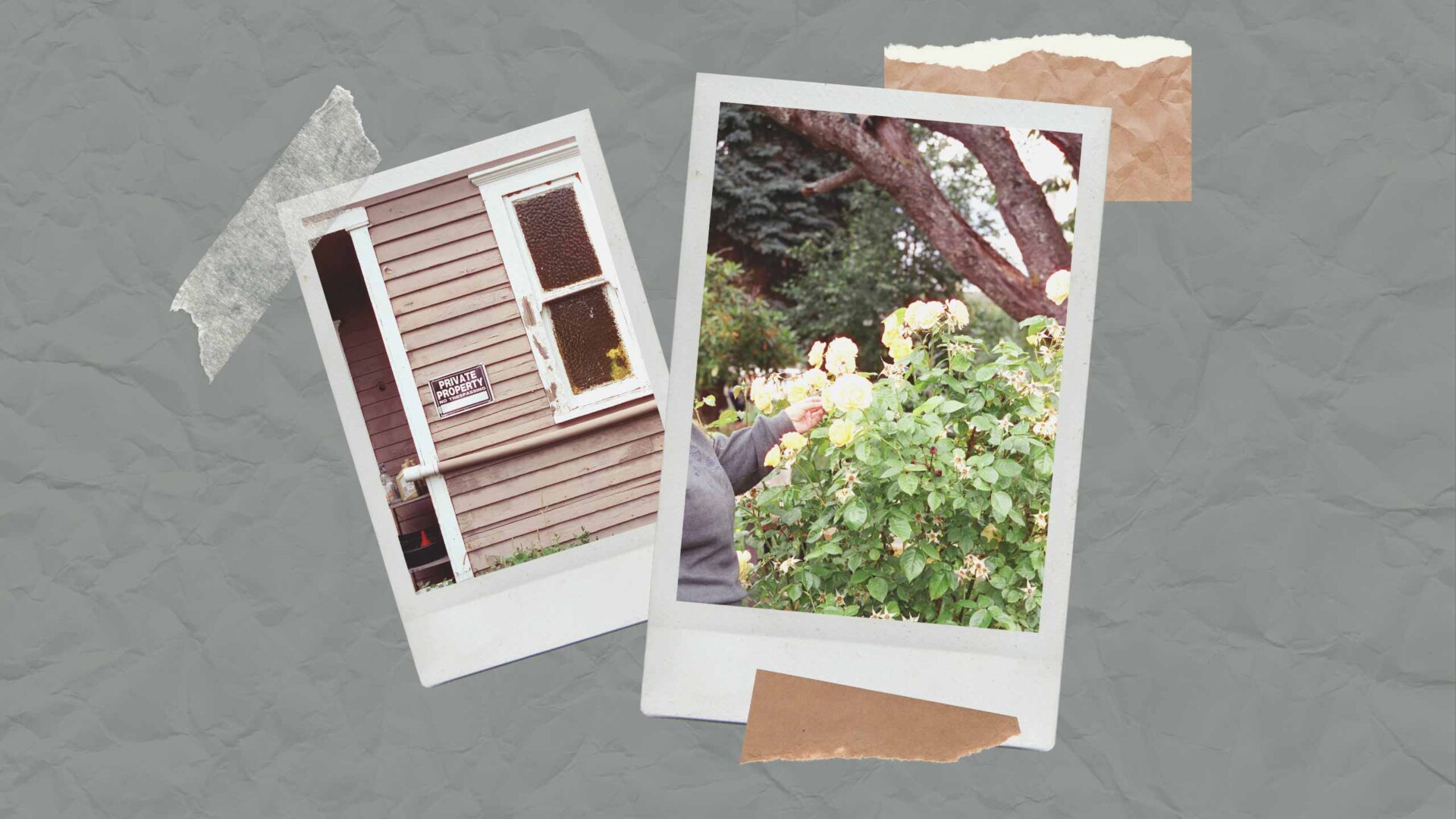

As I worked my way through this film and the reflection, I was sitting inside my own home, set to be demolished in just a few week’s time. As I watched Jimmie love the place he lost before he knew to say goodbye, I thought of the four walls surrounding me, the neighboring homes, the squirrels who crawled into our attic all month long, the rose bush that just bloomed for the last time, a pesky raccoon we’ve affectionately named Ricky, and the community garden plots that house my nosey neighbors who plant seeds every May because they believe the sun will always show up again. I think about the story of this neighborhood and how in a few weeks it will all cease to exist. The city will exchange two homes and a handful of structures dating back a hundred years, for two hundred and ninety apartments. In the two years I have lived in this neighborhood, I have watched block after block be transformed by large rectangular signs announcing that change is coming and with it a reshaping of the ecosystems that currently exist. The story is evolving and with it comes new birth but also, many deaths. I wonder how I’ll keep the story of this place alive. I think of Jimmie caretaking for what was no longer his. What does ownership of a place look like that goes beyond a name on a deed but instead shows up in big and small acts of solidarity through storytelling and taking responsibility for the place you love? For now, I walk my friend through the backyard and ask them to look at the rose bush as it blooms for the last time. Witnessing this small death together feels like the kind of planetary solidarity I envision. This is the background I brought to this assignment.

As is often the theme at The Seattle School, our coursework intersects deeply with the work of our lives. It has been many weeks since the course was complete and yet, I still find myself thinking about how to embody the ecological themes this film showed me. I continue to dream up what commitment and imagination can look like in my own neighborhood as I hold on to a story of a place I’ve loved and lost, too, with a dream that we can each experience the belovedness of belonging as we find our way home, again.

photo credit: Olivia Campbell, MACP 2023